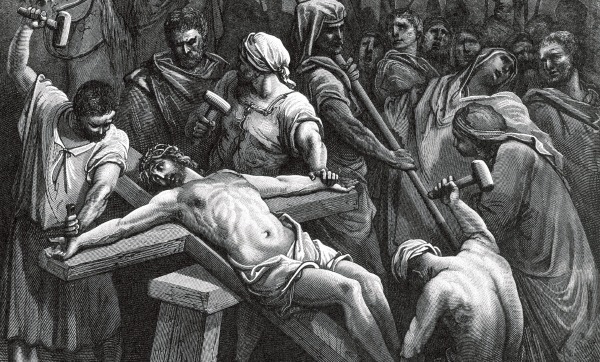

Jesus was a unique priest. He was both a priest and the sacrifice that the priest offered. His priesthood is from the order of Melchizedek, but His sacrifice is patterned after the annual sacrifice of the Aaronic priesthood on the Day of Atonement. In this section (9:1–10:18), Paul returns to that crucial event of Christ’s “offering up himself” (7:27) on the cross in sacrificial death for mankind. Some might think that this section of the epistle is non-sequitur, or that there is a regression as Paul moves from the eternal priesthood of Jesus back to the historic sacrifice of Christ on the cross. Paul’s logic follows the chronologic sequence of the old covenant narratives – the historic progression from Melchizedek to the Mosaic guidelines of the Aaronic and Levitical priests and their practices in the tabernacle and temple. As Melchizedek predates Moses, so the progression of Paul’s thought moves from the eternal Melchizedekian priesthood to Christ’s historic sacrifice of Himself as the singularly sufficient sinless sacrifice for the sins of mankind. By establishing and reiterating the superiority of Christ’s priesthood and sacrifice, Paul continues to encourage the beleaguered Christians of the Jerusalem church in the middle of the seventh decade of the first century not to succumb to the inferior and antiquated practice of the Jewish religion, as advocated by those who wanted to restore such by ousting the Romans from Palestine. Paul knew it was so important for the Judean Christians, who were socially under siege by their religious kinsmen and nationalistic countrymen to join the insurrection against Rome, to “think outside of the box” – to realize that the objects and practices in the “temple-box” that was still standing in Jerusalem were intended by God to be merely illustrative of the permanent access to God that was effected only in the work of Jesus Christ. Within the context of the “new covenant” (8:8,13; 9:15; 12:24) all of the practices of the old system of Judaic religion became antiquated and obsolete (8:13), displaced and replaced. Perhaps the Christians of Jerusalem were questioning: Why, then, is the temple still standing? Why is the Jewish priesthood still functioning? Why are sacrifices still being offered by the priests in the temple? Paul explained that the Jewish practices were outmoded and in decline, and the entire religious system was “near to disappearing” (8:13) – a rather prophetic anticipation of what would transpire in only a few years when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and the “temple-box” in 70 AD. Paul’s objective in this section is to walk his readers through the details of the tabernacle/temple system of sacrificial worship in the old covenant, and to point out the superiority and supersession of such in the redemptive work of Jesus Christ. Any thought of returning and reinvolving themselves in the sacrificial practices of the temple and its priesthood would be an unthinkable, abominable reversion to the imperfect and inadequate practices of the old covenant, which were only intended to be provisional and temporary, preliminary to the perfection of forgiveness and access to God afforded by the Son, Jesus Christ. To return to the Judaic worship practices – to consider the temple sacrifices to be of any value – would be to deny all that Jesus accomplished in His priesthood and sacrifice. To engage again in the restricted access of the “temple-box” after Jesus had opened unrestricted access to the Holy of Holies of God’s presence (cf. 10:19) to all Christians would be to try to “put God in the box” again. May it never be! The “place” (cf. Jn. 14:2) that has been prepared for Christians, “near to the heart of God,” has been opened forever in the “new and living way” (10:20) of Jesus Christ in the “new covenant.” By extension we might add that any attempt by Christians in any age to rebuild and reconstruct the Jewish temple, and to restore and reinstitute the cultic activities of Jewish priesthood and sacrifices, would also be an abominable affront to God’s redemptive work in Jesus Christ. Paul tells the Judean Christians of the first century and Christians in every subsequent century that they must never go back to the insufficient objects and practices of the old covenant, having accepted Jesus as “the better sacrifice, sufficient for forgiveness,” allowing for unrestricted eternal access to God. 9:1 Paul lays the groundwork (9:1-10) for emphasizing the all-sufficient sacrifice of Jesus by reviewing the historic and physical details of the tabernacle in the old covenant. The progression of his thought begins with the context of the two chambers of the tabernacle (9:2-5), and moves to the regulated religious activities within those two chambers (9:6,7). First the places, then the practices. First the setting, then the sacrifices. First the logistics, then the liturgy. First the furniture, then the functions. Making a transitional connection, Paul resumes his argument for the superiority of the “new covenant” (8:8,13) by writing, “Indeed, even the first (covenant) had regulations of worship and the holy place of this world.” Though “the first” has no qualifier, the immediate preceding context (8:13) dictates that Paul is referring to the proto-covenant, the first covenant, the old covenant, the Mosaic covenant of Law, and not to “the first tabernacle” as some interpreters have suggested, even though “first covenant” and “first tabernacle” are connected (cf. 9:6) in this paragraph. The paragraph begins and ends with the concept of “regulations” (9:1,10). The old covenant certainly had rules and regulations for the proper administration of all activities in the tabernacle and temple. God had carefully directed (cf. Exodus 25-31; 35-39) the legal guidelines for the “right way” of doing things in the Jewish worship center. There was a proper way to place the furniture and a proper way to engage in every worship practice. The word Paul uses for “worship” conveys the idea of “serving God in subservience.” By referring to the tabernacle as “the holy place of this world,” Paul is indicating that the Jewish worship center was tangible, terrestrial and temporary. It was material and man-made, in contrast to “the perfect tabernacle of God, not made with hands” (8:2; 9:11). The physical tabernacle was earthly and this-worldly in contrast to the heavenly tabernacle (8:1; 9:23,24) which is “not of this creation” (9:11), and served as the pattern from which the earthly was but a picture (8:5). Paul is already alluding to the inferiority and insufficiency of the Jewish “holy place” or worship center, in order to explain its limited significance. 9:2 Beginning his review of the old covenant worship place, Paul wrote, “For there was a tabernacle prepared,…” The precise regulations for the construction of the original worship tent are recorded in Exodus 26. Though Paul uses the word “tent” which indicates a temporary enclosure, his references to the tabernacle as “the holy place of this world” (9:1) is surely inclusive of the more permanent extension of the Jewish worship center in the subsequent constructs of the Jewish temple. Paul refers to the tent of the tabernacle to connect the Jewish worship center to the original establishment of the old covenant and Moses’ instruction for the construction of the portable tabernacle (Exod. 25:40; Heb. 8:5). Solomon’s temple (I Kings 6), the second temple which was rebuilt after the exile (Ezra 3:8–6:15), and Herod’s reconstruction of the temple (John 2:20), though constructed of more permanent materials, were just as temporary as the tabernacle tent when compared to the eternal and heavenly dwelling place of God (8:1,5; 9:11,23,24). Paul wanted the Jewish Christians in Jerusalem to realize that the Jewish worship center of the tabernacle (and its later extension in the temple which still stood in Jerusalem) was temporary and transient, but the heavenly dwelling place of God was eternally opened up for direct access to God in Jesus Christ. In just a few years, in 70 AD, the temporarily of the Jerusalem temple would be made evident when it was totally destroyed by the Roman army. Both the tabernacle and the temple were constructed in a bipartite design with two compartments or chambers. There was “the first one, in which (were) the lampstand and the table and the setting forth of the loaves.” The first room or chamber in the tabernacle/temple housed the lampstand on the south side of the enclosure (cf. Exod. 25:31-39; 26:35; 37:17-24). The menorah (the Hebrew word for the lampstand) was a candelabrum with seven candles, three on each side of a single upright post. Though there was only one menorah in the original tabernacle (Exod. 25:31), there were ten such lampstands in the temple of Solomon (I Kings 7:49), but Josephus mentions only one in the first-century temple (5.216). On the north side of the first chamber of the tabernacle and temple was the table of showbread on which the loaves were displayed (cf. Exod. 25:23-30; 26:35; 37:10-16). The loaves were replaced either daily (cf. II Chron. 13:11) or weekly on the Sabbath (Lev. 24:8). Jesus, the Bread of Life (John 6:35,48), indicated His superiority and divine privilege over the Sabbatarian rules concerning the temple showbread (Matt. 12:4; Mk. 2:26; Lk. 6:4). “This (first chamber) is called the holy place,” Paul explained in his recapitulation of the architecture of the tabernacle (cf. Exod. 26:33). 9:3 “And after the second curtain there was a tent which is called the Holy of Holies,…” At the entrance to the first compartment there was a curtain or veil or screen (cf. Exod 26:36; 36:37) through which the priests passed into the “holy place” (9:6). Between the “holy place” and the second compartment there was a much heavier curtain or veil (cf. Exod 26:31-33; 36:35; 40:3,21) through which only the high priest entered once a year (9:7). Behind the second curtain “there was a tent,” i.e. a temporary enclosure which was the rear chamber of the larger tabernacle-tent. This back-room was called “the Holy of Holies” (cf. Exod 26:33) or “the Most Holy Place” (cf. I Kings 8:6). This was the place where the holy presence of God was thought to be contained in the old covenant worship center of the tabernacle and temple. 9:4 Paul’s list of the objects that were in the Holy of Holies chamber is problematic. He begins by indicating that the Holy of Holies “had a golden altar of incense.” In the Old Testament narratives the altar of incense seems to have been located in the front chamber of the “holy place” in front of the second curtain (cf. Exod 30:1-10; 40:26). When Solomon constructed the temple the altar of incense may have been placed in the inner chamber of the Holy of Holies (cf. I Kings 6:21,22). Since the physical tabernacle was patterned (8:5) after the heavenly sanctuary, it might be noted that John saw “the golden altar before the throne” (Rev. 8:3) in the heavenly dwelling place of God. The centerpiece of the furniture in the Holy of Holies was “the ark of the covenant covered on all sides with gold…” This was the most important object in the inner chamber. It was a sacred chest made of acacia wood and covered with gold, having rings of gold on each corner so staves could be placed through the rings for transportation (cf. Exod. 25:10-26; 37:1-5). The “ark of the covenant” chest was designed primarily to contain “the tablets of the covenant,” i.e. the “testimony” (Exod 25:16,21) of God, the replaced tablets given to Moses on which were inscribed the Ten Commandments (Exod. 34:28; Deut. 10:1-5). In another variance from the Old Testament accounts, Paul seems to indicate that “a golden jar containing the manna, and Aaron’s rod which budded” were also placed within the sacred box of the “ark of the covenant.” The Mosaic account indicates that a sampling of “the bread from heaven” (Exod. 16:4), the manna provided to Israel in the wilderness, was placed within a jar that was to be placed within the Holy of Holies, but in front of the ark (Exod. 16:31-34) rather than inside of the ark. Likewise, Aaron’s rod which had budded and bore almonds was to have been placed within the Holy of Holies in front of the ark (Numb. 17:1-11), but not within it. Are these variances in the placement of the temple objects to be considered as contradictions in the Scriptures? Not necessarily, for in the long history of the Hebrew people and their worship centers there were no doubt different placements of sacred objects and movements of the furniture. (Cf. diagrams of the tabernacle/temple.) It was noted earlier (9:2), for example, that Solomon had ten lampstands in the “holy place” when he tripled the size of the temple structure. 9:5 Paul continues his brief explanation of the furniture and objects within the Holy of Holies. “And above it (the ark of the covenant) were the cherubim of glory overshadowing the mercy seat.” The top or lid that covered the ark of the covenant was a golden slab that was called “the mercy seat” (Exod. 25:17-22). It was on this lid covering the chest that the high priest sprinkled the blood of the bull and the goat on the annual Day of Atonement (Lev. 16:14-16), as a “covering” for his own sins and the sins of the Hebrew people. Paul’s argument was that the merciful, propitiatory satisfaction of God had been made once and for all in the sacrificial death of Jesus Christ (cf. Rom. 3:25), allowing for an atonement reconciliation between God and man that provided genuine cleansing and eternal forgiveness for sins, rather than just a temporary covering of such. At each end of the mercy seat were “the cherubim of glory.” These were sphinx-like figures, both facing inward with their wings arching over the mercy seat (Exod. 25:18-22). These angelic figures represented God’s heavenly shekinah glory residing above the mercy seat (cf. I Sam 4:4; II Sam. 6:2; II Kings 19:15; I Chron. 13:6; Ps. 80:1; 99:1) in the Holy of Holies. Cutting short his description of tabernacle/temple details in order to proceed to the argument at hand, Paul writes, “but of these things we cannot now speak concerning each piece.” The tabernacle objects and furniture, and their particular placements, were of relative importance to what Paul had to say. They were just the stage setting. And if Paul did not deem it necessary to explain all the details of the usage of each object, and the possible figurative or typological meanings of each piece, neither should we! The two chambers or compartments of the Jewish worship center, and the practices that took place with them, provide the framework for the point that Paul seeks to make. 9:6 “Now these things (the objects of 9:2-5) having been arranged, the priests keep going into the first tent, performing the worship.” The Levitical priests continually entered into the first chamber of the tabernacle and temple to perform and accomplish their subservient service of worship unto God. They trimmed the lamps of the menorah (Exod. 27:20,21), burned incense on the altar (Exod. 30:7,8), and replaced the loaves of bread on the table (Lev. 24:8,9). The present tense verb that the priests “keep going” into the chamber of the “holy place”, likely indicates that this activity was still taking place at the time when this epistle was written. 9:7 “…but into the second (chamber) only the high priest (enters), once a year,…” Contrasting the worship practices in the two compartments of the tabernacle and temple, Paul notes that only the high priest of the Aaronic high priesthood (cf. discussion in the introductory comments to 4:14–5:10) was supposed to enter the Holy of Holies, and that on only one day of the year, the Day of Atonement (Lev. 16:3-24). There was an exclusive limitation of entrance into and access unto the presence of God in the Jewish worship practices. Paul will use the singularity of the high priest’s entry on the Day of Atonement to point to the singularity of Christ’s self-sacrifice (7:27; 9:12,26,28; 10:10), providing open access to all who are in Christ into the Holy of Holies of God’s presence (10:19-22). The high priest entered the Holy of Holies annually, but “not without blood, which he offers for himself and for the ignorances of the people.” The purpose of the high priest going into the Holy of Holies on the Day of Atonement was to sprinkle blood on the mercy seat lid of the ark of the covenant. He actually entered the second chamber twice on that day, first to apply the blood of a bull on and before the mercy seat, to cover the sins of himself and his household (Lev. 16:11-14), and second, to sprinkle the blood of a goat on and before the mercy seat to cover and make atonement for the sins of the people of Israel (Lev. 16:15,16). Although the atonement sacrifice was for “all the sins” of Israel (Lev. 16:34), rabbinic interpretation had restricted its application to only unintentional or unknown sins committed in ignorance, allowing no remedy for intentional sins. It is apparently this popular and traditional interpretation that Paul refers to. The sacrifice of an animal in death, and the application of the blood before God, was regarded as having a cleansing and purging effect for the impurities of the people (Lev. 16:16). Paul adroitly refers to the high priest as “offering” the blood, even though the Old Testament refers to “sprinkling” or “applying” the blood, as this corresponds to Christ’s “offering” of Himself (9:14, 25-28; 10:10,12,14) as the sacrifice sufficient for spiritual cleansing and forgiveness. The necessity of blood (cf. 9:18,22) is explained by the need for a counteraction of the death consequences of sin. Can you imagine what the mercy seat, the cover-lid of the ark of the covenant, must have looked like, caked with layer-after-layer of blood year-after-year? Can you imagine how it must have smelled? Can you imagine how the flies and the maggots must have been present in the heat of the desert? Perhaps the burning of incense served another purpose other than just representing reverence and honor unto God, i.e. providing a fragrance to offset the stench. 9:8 Paul now begins to draw his conclusions in this paragraph. Based on the personal revelation of God’s Spirit to Paul, he explains that “The Holy Spirit is signifying this” by the difference between the two chambers of the tabernacle/temple and the worship practices that transpired within them. Paul sees a parallel between the “first chamber” (9:2,6,8) of the tabernacle and the “first covenant” (8:7,13; 9:1,15,18), the “old covenant” (cf. II Cor. 3:14); and between the “second chamber” (9:7) of the tabernacle and the “second covenant” (8:7), or “new covenant” (8:8,13; 9:15; 12:24). The first compartment of the “holy place” was a figure of the temporal, old covenant Jewish religion. The second compartment of the Holy of Holies prefigured the sacrifice of Jesus Christ and the new covenant access into the eternal and heavenly presence of God’s glory. Only when the physical, old covenant, Jewish worship center of the temple was destroyed and eliminated would the eternal significance of open access into the Holy of Holies of God’s heavenly presence be fully realized by the Judean Christians who were the recipients of this letter. The spiritual significance, Paul writes, is “that the way into the Holies has not yet appeared while the first tent has standing, which is a parable unto the present time.” Jesus Christ alone is the only “way” into the holy presence of God (John 14:6). But this had not become manifestly apparent to the Christians of Judea. The physical temple was still standing in Jerusalem, claiming to offer an indirect access to God once a year through the high priest’s actions on the Day of Atonement. The Christians in Jerusalem were still tempted to give credence to the Jewish worship practices – to regard them as having status, value and worth. The tabernacle/temple system of the old covenant still had “standing” and respect in the eyes of many of the Jewish Christians. Not until that “first tent,” the physical temple (both the first chamber and the second chamber) was destroyed (as it was in 70 AD) would the insufficiency of Jewish worship become apparent, and the full significance of access into the eternal Holy of Holies be disclosed and revealed to the Christians to whom Paul was writing. So the temple that still stood in Jerusalem, with its two worship chambers, served as a parabolic illustration, a symbolic analogy, for those Christians who were at that “present time,” in the middle of the seventh decade of the first century, the mid 60s, struggling to give full allegiance to Jesus Christ. Paul wanted them to move into the full experience of the “second chamber” within the “second covenant”, i.e. the “new covenant” of Jesus Christ. While the old temple still stood and had “standing” in the minds of the people, the way to God was still pictorially blocked and barricaded by the veil that separated the Holy Place from the Holy of Holies. The sacrifice of Jesus Christ on the cross had caused the veil in the temple to be “torn in two from top to bottom” (Matt. 27:51; Mk. 15:38; Lk. 23:45), signifying that the separation of God and man had ended. Those who accepted Christ’s offer of life could “enter within the veil” (6:19), “having confidence to enter the holy place by the blood of Jesus, by a new and living way which He inaugurated through the veil, that is, His flesh” (10:19,20). This is what Paul wanted the Christians in Jerusalem to understand and to live by. 9:9 Paul continues by explaining that, “In accord” with the imperfect symbol of the still-standing temple that still claimed to be the only proper place to worship God, “both gifts and sacrifices are offered which are not able to perfect the conscience of the one worshipping.” In accord with the old covenant worship practices, gifts and sacrifices were still offered in the temple at Jerusalem, but there was no divine dynamic of God grace provision in those “works” activities to bring about the intended objective and purpose of God. “The Law made nothing perfect” (7:19). The legal requirements of Judaic worship were unable to cleanse from sin (9:13,14; 10:2), to effect forgiveness (10:4,11), to make one perfect (10:1), or to provide direct access to God. Those who participated in such religious actions knew in their inner conscience that there was still evil (10:22) and a “consciousness of sins” (10:2) that had not been cleansed (9:14). There was still a haunting emptiness of loneliness and alienation that hindered their “drawing near to God with a sincere heart in full assurance of faith” (10:22). F.F. Bruce remarks, “The really effective barrier to a man’s free access to God is an inward and not a material one; it exists in his conscience. It is only when the conscience is purified that a man is set free to approach God without reservation and offer His acceptable service and worship.”1Paul wanted his Christian kinsmen in Judea to see through and beyond the Jewish worship practices, and to “serve the living God” (9:14) with a clear conscience that allowed them to enter in and worship God directly and intimately in the fullness of His holy presence. 9:10 The gifts and the sacrifices of the old temple worship, and all of the old covenant regulations of Jewish life, “because they are only upon food and drink and various washings, are but regulations of the flesh being imposed until a time of setting things straight.” The peripheral externalities of the right and proper way to do everything that were imposed by the Jewish Law (cf. Lev. 11 for food laws) were but “a shadow of things to come” (Col. 2:17). They were not beneficial to spiritual development (Heb. 13:9), and were “of no value against fleshly indulgence” (Col. 2:23). Jesus had confronted the Jewish leaders about such “food and drink and washings,” referring to their religious regulations as “precepts” and “traditions of men” (Mk. 7:1-15). Paul calls them “regulations of the flesh,” meaning that they pertain to physical matters, but cannot provide any cleansing of the conscience (9:14). Such earthly and human rules and regulations certainly do not effect the heavenly realities that Paul is pointing his readers towards. The Palestinian revolutionaries, who were using religious issues as a rallying cry, were tempting the Judean Christians to put stock in such religious regulations, and this is what Paul wanted to forestall. The temporality, transience, and impermanence of such bodily regulations is evidenced by Paul’s statement that they are only “being imposed until a time of setting things straight.” The old covenant religion was out-dated, antiquated, and obsolete (8:13). Paul anticipated that time when the misunderstanding of worship and behavior in Judaism would be rectified and corrected. He is not referring to a time of “reformation” when Judaism would be “re-formed,” reconstituted, or restored. That was the stated objective of the insurrectionists fomenting war against the Romans. Paul was adamant that Christianity was not a “re-formed” Judaism, but was a radically new reality of the living Lord Jesus in mankind. “The time when things would be set straight” would come in 70 AD when the Christians to whom Paul was writing would realize that all the worship practices and all the behavioral regulations of Judaism were totally defunct, and that Jesus Christ was indeed “the only way into the Holy of Holies” (9:8) of God’s presence for all worship and life. 9:11 This verse commences the second major section (9:11-28) of Paul’s argument concerning Jesus as the better sacrifice (9:1–10:18). The first section (9:1-10) provided the stage-setting of his theme, by considering the two compartments of the Jewish worship center, with their distinct fixtures (9:2-5) and differing functions (9:6,7), followed by an explanation of their significance (9:8-10). This second section (9:11-28) considers both parallels and contrasts between the sacrifices of the Jewish old covenant and the superior Self-sacrifice of Jesus Christ. It seems to be divided into three subsections or paragraphs: [1] sacrificial blood and cleansing (9:11-14) [2] sacrificial death and covenant (9:15-22) [3] sacrificial singularity and salvation (9:23-28). In the old covenant worship, the high priest arrived at the temple on the Day of Atonement to apply the blood of the representative animal sacrifices in order to cover the sins of himself and the people of Israel (9:7) until the promised fulfillment of all that was yet to come by the action of the Messiah deliverer. Contrasted with this, Paul writes, “But Christ having arrived as High Priest of the good things having come,…” Christ, the promised Messiah, arrived at His heavenly destination (cf. 7:26; 8:2; 9:12,24) as the eternal High Priest after the order of Melchizedek (6:20; 7:1-17). But in likeness with the Aaronic high priests, He entered the Holy of Holies to make a representative sacrificial offering for the sins of the people. As an absolutely unique High Priest, He served as both the priest and the sacrifice. Whereas the Jewish high priests offered sacrifices on the cover of the mercy-seat which were but a temporary covering for impurity, anticipating more permanent “good things to come” in the future, the Messiah-Priest brought those “good things” of God into being in fulfillment of all the promises (cf. II Cor. 1:20). The anticipated “good things to come” are now the completed “good things having come.” This is the difference between Jewish eschatology and Christian eschatology. All that was anticipated and expected in the old covenant has now been made available for viable spiritual experience in the living Lord Jesus. All of the “good things” – all of the “better things” that this epistle points to – have historically (ex. crucifixion, resurrection, ascension) and theologically (ex. Redemption, salvation, sanctification) and personally or experientially (ex. Forgiveness, cleansing, perfection, access to God) been brought into being in Jesus Christ. Christ entered “through” the veil (10:20) and into “the greater and more perfect tent not made with hands, that is, not of this creation.” Jesus Christ serves as the High Priest in the heavenly chamber (9:3,6) of God’s presence (cf. 4:14; 8:2; 9:24) – the superior dwelling place of God that achieves the real end-objective of God’s intent for man, i.e. allowing man into His presence, and His presence into man. This worship place is obviously not man-made (cf. Isa. 66:1) of physical materials (cf. Mk. 14:58; Acts 7:48; 17:24; Heb. 9:24), but is “the tabernacle of God” (Rev. 21:3) “pitched by the Lord” (8:2). This dwelling place of God “in heaven itself” (9:24) is “not of this creation,” thus it cannot be identified with any physical temple in Jerusalem, nor can it be identified as the physical body of Jesus (cf. Jn. 1:14). The heaven-chamber is not subject to shaking (12:26-28) or perishing (1:11), for it is not part of the natural creation, and Paul wanted the Jerusalem Christians who were reading this epistle to take their eyes off of the physical temple and its practices which would indeed be shaken and perish in the very near future. 9:12 Jesus Christ, the Messiah-Priest, entered the heaven-chamber of the divine presence “not through the blood of goats and calves, but through His own blood.” The medium of access for the Christic high Priest was not the blood of animals, as it was for the Aaronic high priests (9:7) who offered animal sacrifices annually on the Day of Atonement in the tabernacle in the temple in Jerusalem. Jesus accessed heaven by a unique and superior representative sacrifice, i.e. “through His own blood,” which served as the instrumental means allowing all who accept His representation to enter God’s presence “in Him.” Reference to “the blood of Jesus” (9:12,14) does not necessarily refer to the material substance of plasma, corpuscles or platelets of the human blood of Jesus, but rather to the action of Jesus’ sacrificial death,2 for by His death He counteracted the death that had come upon mankind (2:14), and effected the death of death.3 Reiterating Christ’s access into heaven, Paul writes, “He entered the holy place once for all, having secured the redemption of the ages.” Unlike the Judaic priests who entered the Holy of Holies repetitively once every year (9:7,25), Jesus’ entrance into the heavenly divine presence was singular and final. He had secured the liberation of mankind from the clutch of sin and death, finally and forever by the ransom payment (Matt. 20:28; Mk. 10:45; I Tim. 2:6) of His own death, the perfect price paid (cf. I Cor. 6:20; 7:13; I Pet. 1:18,19; II Pet. 2:1) to free mankind from the slavery of sin. His sacrifice in death is validated as satisfactory and sufficient by the securing of the eschatological redemption and “eternal salvation” (5:9) for mankind, confirming divine acceptance and the fulfillment of all God intended for mankind. 9:13 In antithetical contrast to the finality of Christ’s sacrifice, and to emphasize the insufficiency of the ceremonial cleansings of the old covenant, Paul argues, “For if the blood of goats and bulls, and the ashes of a heifer sprinkling those having been defiled, sanctified for the cleansing of the flesh,…” Paul is not doubting or questioning the effects of the old covenant sacrifices, but is affirming the limited efficacy of such when compared to the sacrifice of Christ (14). The blood sacrifice of goats and bulls occurred on the Day of Atonement, but Paul seems to generalize in order to include all old covenant sacrifices (cf. Numb. 7:15,16), particularly inclusive of the sin-offering of the red heifer (cf. Numb. 19:1-22). The application of animal blood by sprinkling was regarded as a setting apart of the objects or persons that had been defiled, polluted, or made impure, in order to cleanse them of their physical defilement and make them available for God’s holy purposes. These religious rituals of ceremonial cleansing had limited efficacy, for they were only a temporary and external “cleansing of the flesh,” i.e. of the outward and physical defilement and corruptions, and could not deal with the internal conscience and its consciousness of sin. 9:14 The superior and surpassing efficacy of Christ’s sacrifice is exclaimed, “…how much more will the blood of Christ, who through the Spirit of the ages has offered Himself without defect to God, cleanse your conscience from dead works unto worship of the living God.” The new covenant is not established on the blood of animals, nor even on the blood of a martyr, but on the representative sacrifice of the Messianic Son of God. The “blood of Christ” once again (12) refers not to some mystical efficacy of the material substance of Jesus’ blood, but to the representative death of Jesus. Divinely empowered by the Holy Spirit (cf. Lk. 4:18), “the Spirit of the ages,” Jesus actively, willingly (10:5-10) and obediently (cf. 5:8,9; Phil. 2:8) offered Himself (7:27), serving as both the priest and the sacrifice. His was a voluntary sacrifice (cf. Jn. 19:30), whereas the animals of the old covenant were sacrificed involuntarily and passively. But like the animal sacrifices which were to be without spot, blemish or defect (Lev. 1:3,10; 22:18-25; Numb. 19:2; Deut. 17:1), Jesus was “without sin” (4:15; II Cor. 5:21), “holy, innocent, and undefiled” (7:26), the sinless sacrifice sufficient to deal with the internal and spiritual separation of mankind from God. Whereas the animal sacrifices could only assuage the external defilement in a ceremonial “cleansing of the flesh” (13), the representative death of Jesus can “cleanse your conscience from dead works.” The Jewish rituals could not deal with the internal cleansing or perfecting of the conscience (9:9; 10:2). Sin, and its consequence of death, is much deeper than external defilement and behavioral transgression. Only Jesus’ death can “cleanse the conscience” from the guilt of sin and the condemnation of thinking one has to pay or offer something to appease and please God. Religion, on the other hand, capitalizes on this nagging need of performance “works” to “measure up” and “get right” with God, advocating that their adherents go through the motions of endless rituals and confessional cleansings to feel connected to God. To the Romans, Paul wrote, “There is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Rom. 8:1). On the basis of Jesus’ death, Christians are reconciled (Rom. 5:10) and have peace with God (Rom. 5:1). The positive side of “cleansing from dead works” is the provision of being “made righteous” (Rom. 5:17,19; II Cor. 5:21) in order to participate in the “good works” that God prepares (Eph. 2:10), equips (Heb. 13:21), and supplies sufficiency for by His grace (II Cor. 9:8). Paul did not want the Hebrew Christians in Jerusalem to be conscientiously bound to their past worship practices, or to revert back to the ineffectual temple rituals of Judaism, which were but the “dead works” of religion. He wanted them to operate out of a cleansed conscience, a “good conscience” (13:18; I Pet. 3:21) that did not wallow in the “consciousness of sins” (10:2). He wanted them to recognize their freedom “to worship the living God” in spiritual worship (cf. Jn. 4:24; Rom. 12:1), accessing the Holy of Holies of God’s presence transcendently and immanently. 9:15 In this second subsection (9:15-22) the sacrificial death of Jesus is connected to the concept of “covenant.” In the previous study of “JESUS: the Better Minister of the New Covenant” (8:1-13), background material was presented concerning the ancient practices of “blood covenants,” and the Hebrew concept (berith) of God’s establishment of unilateral covenants with mankind. Paul took the prophecy of Jeremiah 31 concerning a “new covenant” and explained that this involved an internalization of God’s Law upon the hearts and minds of His people (8:10; 10:16). Consistently, Paul continues his present argument, “Through this,” the death of Jesus that allows for the internal cleansing of the conscience and the positive ramifications of reconciliation, justification and spiritual union, along with experiential peace and assurance, “He is the mediator of a new covenant,…” The old Jewish covenant explained in the Old Testament was obsolete and antiquated (8:13), nullified and abrogated (7:18; 10:9). The new covenant promised through Jeremiah (Jere. 31:31-34) was inaugurated by the death of Jesus, and that is why Jesus explained that the Eucharist observance represented “the new covenant in My blood” (Matt. 26:28; Mk. 14:24; Lk. 22:20; I Cor. 11:25). The new covenant (7:22; 8:6,8; 10:16; 12:24; 13:20) was the new arrangement, agreement, and settlement that God had “put through” in His Son, Jesus Christ, who was the mediator (8:6; 12:24), the one who “stood in the middle” between God and man as the God-man, “the one mediator between God and man” (I Tim. 2:5), to effect and enact what was God’s intent for man from the beginning. The means of Jesus’ mediatorial enactment of a new covenant is explained, “so that a death has occurred for the redemption of the transgressions at the time of the first covenant,…” The inadequate animal sacrifices of the old covenant have been superseded by the historical representative death of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who effected the purchased losing and liberation of redemption (9:12; Eph. 1:7), the buying back of mankind by the price of His own death (I Cor. 6:20; 7:23), even from the consequence of the transgressions that occurred at the time of and under the regulations of the first covenant (cf. Rom. 3:25). The result of Jesus’ mediatorial enactment of a new covenant is explained, so that “those having been called might receive the promised fulfillment of the inheritance of the ages.” The “calling of God” (Rom. 11:29; Eph. 1:18) to Himself is in the Person and work of Jesus Christ, who as “the Elect One” (Lk. 23:35) is the basis and dynamic of the divine effectual calling. “Those having been called” are all those who have responded to God’s calling in Jesus Christ and received Jesus Christ (cf. Jn. 1:12,13), and in so doing may/should receive (not a future tense) the fulfillment of the promises of the eschatological inheritance of all the blessings of the new covenant “in Christ” (cf. Eph. 1:3). This inheriting (1:4) of the “eternal salvation” (5:9) involves becoming heirs that inherit the fulfillment of all God’s prophetic promises in the old covenant (6:12,17), an inheritance that is “imperishable and undefiled and will not fade away” (I Pet. 1:4). This inheritance is not just a future expectation, but is the fullness of Christ experience “already” in the present, with a “not yet” consummation in the future. It is here that we must address the most problematic issue in this passage. Paul’s reference to “covenant” (15,16,17,18,20) has been interpreted in several ways due to the divergent Hebrew and Greek concepts of “covenant” that existed in the first century. The Hebrew word berith was used for both bilateral agreements between persons, and for the unilateral arrangements that God established with man. The Greek language had two separate words: suntheke (“to put together with”) for bilateral agreements, and diatheke (“to put through”) for the unilateral arrangements of a “last will and testament.” Since the Greeks had no theological understanding of divine unilateral arrangements, the word diatheke was never used for such. But when the Jewish people of the Middle East began using the Greek language as their medium of expression, the only viable word for a unilateral arrangement was diatheke, and they employed the word in reference to God’s unilateral covenants. When Jesus, and the subsequent Christian community, began to refer to the “new covenant” in Christ, they also employed the available Greek word diatheke. So, the Jewish and Christians communities were using the word diatheke in a way that it was never used in the Hellenistic community. The question before us is: How did Paul (who grew up as a Jew in the Hellenistic community of Tarsus, and then became a Christian) use the word diatheke in this particular passage of his epistle to the Hebrews? Some have concluded that all references to diatheke in this paragraph refer to the original Greek concept of a “last will and testament.” Others have concluded that all references to diatheke in this paragraph refer to the Jewish concept of a divine unilateral ‘covenant” of God with man. Still others, have concluded that Paul jumps back and forth, switching his meaning from “covenant” (15), to “last will and testament” (16,17), and then back to “covenant” (18,20); or even more ambiguously, integrating the concepts in a merged double entendre. Though the mention of “inheritance” (15) could create a legal connection to the Greek idea of “testament” in the following verses (16,17), it will be our contention in the following comments that Paul, a Hebrew Christian, writing to his fellow Hebrew Christians in Jerusalem, retains a Hebrew concept of berith in his use of the Greek word diatheke, and that the concept of a unilateral “covenant” of God predominates throughout this passage. 9:16 Continuing to explain Jesus as “the mediator of a new covenant” (15) – and let it be noted that mediators were not necessary for a “last will and testament” – Paul writes, “For where there is a covenant a death is necessary to be represented by the one covenanting.” As the ancient covenants were almost exclusively “blood covenants,” usually requiring the death of a sacrificial animal to ratify the agreement, so God’s covenants utilized the confirmation validation of sacrificial death (18). The Hebrew word berith was derived from the word bara, meaning “to cut,” and the one covenanting was regarded as “cutting a covenant,” which involved the cutting and death of a representative sacrifice. A “covenant,” in the Hebrew sense of the word, required a representative death performed by the one cutting the covenant in order to seal the covenant. The Greek concept of “testament” does not make sense here, for the testator’s death was not necessary in order to make a “last will and testament.” 9:17 Explaining a general principle of covenants, Paul continues, “For a covenant is ratified upon corpses, since it is not even binding as long as the one covenanting (allows the sacrifice) to live.” God speaks through the Psalmist, of “those who have made covenant with Me by sacrifice” (Ps. 50:5), thus stating the same covenant principle of sacrifice and representative death. Covenants were ratified and confirmed “upon corpses.” Usage of the Greek term nekrois, “corpses,” had no known usage in reference to “last will and testaments” in Greek literature. Its usage here refers to dead bodies, whether animals or men, but there is nothing in the word itself that requires it to refer to humans. Covenants (bilateral or unilateral) were not regarded by the Hebrews to have any strength for binding enforcement as long as “the one cutting the covenant” allowed the representative sacrifice to live without the cutting that led to blood and death. It must be admitted that in the Greek text the verb “lives” appears to connect with the subject of “the one covenanting,” rather than to the one being sacrificed, which leaves the door open for an interpretation of “testator death” instead of the representative death of a sacrifice. But all the other words and grammar in this paragraph seem to point to the idea of “covenant” rather than “testament.” 9:18 Moving from the general principle (16,17) to the particular of the inauguration of the old covenant, Paul wrote, “This is why the first (covenant) was not initiated without blood.” The first covenant, the “old covenant,” the Mosaic covenant of Law, was not inaugurated, confirmed, validated or ratified, so as to become legally binding, without representative blood sacrifice. The sacrificial blood of a representative death established, confirmed, sealed, and made the covenant agreement effectual. 9:19 The historical occasion of the establishment of the old covenant by sacrificial blood is recorded in Exodus 24:3-8. Paul reviews this, “For when every commandment according to the Law had been spoken by Moses to all the people, taking the blood of calves, with water and scarlet wool and hyssop, he sprinkled both the scroll itself and all the people.” The Old Testament text does not mention the blood of goats, only of bulls, and the oldest manuscripts of the Greek text of this epistle (dating to approximately 200 AD) do not contain the word “goats” either. The primary variance, then, is Paul’s addition of applying the blood “with water and scarlet wool and hyssop.” This is not recorded in Exodus 24, but these items were sometimes used for the application of blood sacrifices on other occasions (cf. Lev. 14:4-7, 51,52; Numb. 19:6). Though Exodus does not specifically indicate that the blood of the bulls or calves was applied to the “scroll of the covenant,” this may have been part of Jewish tradition that Paul remembered. 9:20 Upon applying the blood for the initiation of the covenant, Moses “said, ‘This is the blood of the covenant which God commanded towards you.’” Paul is quoting this statement of Moses from Exodus 24:8, made after the Hebrew people had accepted the covenant and promised to abide by it. There does not appear to be any veiled allusion in these words to the word of Jesus when taking the last supper with His disciples. 9:21 Paul’s reiteration of the inauguration of the old covenant with blood sacrifices has additional details not recorded in Exodus 24. “And likewise, he (Moses) had sprinkled both the tent and all the vessels of the tabernacle worship with the blood.” When the tabernacle was later erected there was an anointing of the tent and all its utensils with oil (Exod. 40:9,10), but there is no record of such action when the old covenant was established. These utensils and vessels included the shovels and snuffers, and all of the pots, jars, plates, bowls, basins, spoons, etc., which were utilized in the Jewish worship center (cf. Numb. 4:7-12). 9:22 In summary of his argument of God’s Mosaic covenant inaugurated with blood sacrifices, Paul concludes this subsection paragraph, “And according to Law, almost all things are being cleansed by blood, and without the application of blood nothing is pardoned.” In the limited context of the Law covenant, almost all things (but not all), underwent the ceremonial and ritualistic cleansing by blood to remove contamination and defilement. There were situations, though, where the poor could bring a sin-offering of flour (Lev. 5:11), and when defilement could be cleansed with water (Lev. 15:10-12; Numb. 31:23) or with fire (Numb. 31:23). In contradistinction to “almost all things” being cleansed with blood, Paul notes that “nothing” is pardoned without the application of blood. This part of the summary statement is still qualified by “according to the Law,” and refers to old covenant understanding of the expiatory and propitiatory value of blood sacrifices. It is not the release of blood from the animal in blood-letting or blood-shedding that is being referred to, but the blood-pouring ritual application of the sacrificial blood that was regarded as being efficacious for the discharge, pardon or forgiveness or transgressions (15) or sins. The Hebrew word for this atoning action, kaphar, meant “to cover,” and by figurative theological extension, “to place” or “to appease” God in order that He might be satisfied in order to condone, pardon, or cancel the effects of the sin-offense. In the old Mosaic covenant of Law the application of the blood sacrifice of animals was regarded as efficacious for the release of culpability and liability for transgressions of the Law. Paul’s objective in this reiteration of the old covenant application of blood sacrifices was to set up his argument that “it is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins” (10:4), and thus to discourage the Hebrew Christians in Judea from reverting back to their inferior and inadequate worship practices, as were still practiced in the temple in Jerusalem. 9:23 In this third subsection (23-28), Paul returns (cf. 11-14) to the contrasts and parallels between the old covenant sacrifices and the singularly sufficient and final sacrifice of Jesus Christ. “Then, it was necessary for the models of the things in the heavens to be cleansed by these means, but (now) the heavenlies themselves (are accessed) by better sacrifices than these.” Utilizing a “then – but now” contrast, Paul explains that “it was necessary” (cf. 7:12; 9:16), logically, theologically, and particularly legally (22), for the old covenant worship center models or examples (4:11; 8:5) to be cleansed in ceremonial purification from external defilement and contamination, by the means of representative blood sacrifices. The Jewish worship places and practices were but “a copy and show of the heavenly things,” Paul explained previously (8:5), and God told Moses to erect the tabernacle “according to the pattern” (8:5) of the heavenly worship place. For this reason Paul refers to the old covenant worship rooms as “models,” examples, or facsimiles which were both, patterned after the heavenly reality, and prefiguring of the access to heavenly worship in Jesus Christ. The tangible tabernacle and temples were but the temporary, inadequate and imperfect subdemonstration of the heavenly presence and worship of God. The Greek word for “model” or “example” means “to show under,” and could be transliterated as “hypodigmatic.” The “heavenlies,” on the other hand, in contrast to the earthly “models,” are accessed not by ceremonial animal sacrifices, but by the singularly sufficient sacrifice of the representative death of Jesus Christ. The verb action of “cleansing” in the first phrase cannot be inserted as the non-specified verb action of the second phrase in this verse. There is nothing in the heavenlies of God’s presence that requires cleansing, but access to the dwelling place of God did require the cancellation and abolishment of sin by the sacrifice of the Son of God (26). So, the verb action of “entering” access from the following contextual phrase must be supplied as the absent verb in this second phrase. The “better sacrifice” of the death of Christ is the only sacrifice that can “cleanse the conscience” (14) internally, and allow Christians to participate in the “living sacrifice” (12:1) of themselves, and the offering of “the sacrifice of praise” (13:15) for all that was accomplished on our behalf by the Savior. 9:24 Returning to a contrast of the activities of the old covenant Aaronic high priests on the Day of Atonement, Paul explains, “For Christ has not entered the holy places made with hands, an antitype of the real things,…” Again, Paul indicates that the physical tabernacle and temple that were man-made (9:11), temporary and inferior, were but a copy, representation, reproduction, or “antitype” (Greek word antitypa) of the heavenly realities. The following diagram may assist in understanding Paul’s perspective of the contrasts between the heavenly and earthly worship centers:  The divine-human Jesus never physically entered the Holy Place or the Holy of Holies of the temple in Jerusalem, for He was from the tribe of Judah, not Levi; but that is not the point Paul is making. The contrastual point is, “but (Christ has entered) into the heaven itself, to appear in the presence of God on our behalf.” “Heaven itself” is not a cosmological consideration of a spatial locality, but refers to the presence of God where God can be worshipped face-to-face. The Greek word for “presence,” prosopon, means “before the face.” Jesus Christ, crucified, resurrected and ascended, has entered (the verb is supplied from the previous phrase), and now, in the eschatological period of Christian fulfillment, has been manifested and made apparent in the heavenly and glorified presence of God. Not only does His returning entrance into the presence of God allow Him to intercede “on our behalf” (2:18; 4:15,16; 7:25; Rom. 8:34; I Jn. 2:1) as a mediating High Priest, but is also opens immediate access for all Christians who are “in Christ” to “draw near” to the presence of God (4:16; 6:20; 7:19; 10:19,20) in direct face-to-face worship. F. F. Bruce writes, “His entrance into the presence of God is not a day of soul-affliction and fasting, like the Day of Atonement under the old legislation, but a day of gladness and song, the day when Christians celebrate the ascension of their Priest-King.” 49:25 When Christ entered the Holy of Holies of God’s presence, it was “not in order that He should offer Himself often, even as the high priest enters into the holy place annually with the blood of others.” In contrast to the Aaronic high priests, Jesus does not have to offer Himself as a representative sacrifice over-and-over again in the multiplicity of repetition. Using a present tense verb that may indicate the present continuation of the activity of the high priests in the temple at Jerusalem, Paul notes that the high priest enters the holy place, the Holy of Holies, year-after-year in annual repetition, to sprinkle the blood of slain animals (not his own) serving as representative sacrifice to “cover” the sins of the people. 9:26 Jesus is not like the Aaronic high priests, “Otherwise, it would have been necessary (for Him) to suffer often from the foundation of the world;…” If, as is not the case, Jesus had to make repetitive sacrificial offerings of death, as the Jewish high priests had to do, this would have required Jesus to suffer and die repetitively “from the foundation of the world,” i.e. throughout human history. Underlying this statement of Paul may be a presupposition of Jesus’ preexistence (1:2; Jn. 1:1) “from the foundation of the world,” but nowhere does Scripture indicate that Jesus died before the foundation of the world (despite the mistranslation of Revelation 13:8 in the KJV), or that He died repetitively since the foundation of the world. This is patently impossible, for Jesus, the eternal High Priest, made the historic representative sacrifice of death as a man (2:9-16), and Paul would soon note that a man only dies once (27). The counterbalance to the absurd hypothesis of Jesus’ repetitive dying is, “…but now, once, upon the climax of the ages, for the abolition of sin through the sacrifice of Himself, He (Jesus) has been manifested.” In contrast to any hypothesis of a multiple repetitive dying, Jesus as High Priest offered Himself “once and for all” as the singularly unique and sufficient representative sacrifice for mankind. This served as the completing climax and consummation of the ages, the eschatological fulfillment of “the last days” (1:2; Acts 2:17), the “end of the ages” (Matt. 13:39,40; 24:3; 28:20; I Cor. 10:11), serving in the “fullness of time” (Gal. 4:4) to establish the Christian age, the last age, the new age, and fulfill God’s intent for mankind. The High Priest, the Son of God, voluntarily allowing for the sacrifice of Himself, the Sinless One (4:15; 7:26), in a representative death for all mankind, could do far more than cover up sin, as the Jewish high priests did in their ceremonial sacrifices. Jesus could set aside (7:18) sin, put it away (I Jn. 3:5), cancel it, remove it, abolish it, and absolve it by His own death. The God-man, Priest and sacrifice, did just that when He was historically manifested as a man in the incarnation (Jn. 1:14; Gal. 4:4; I Pet. 1:20), and that for the purpose of dying as a man (Matt. 20:28; Mk. 10:45; Jn. 12:27), a representative death to take upon Himself the death consequences of mankind. 9:27 To show the logical relationship and personal application of these themes, Paul writes, “And accordingly, it is laid upon man to die once, and after this judgment.” Because of the fall of man into sin (Gen. 3:1-7), the death consequences (Gen. 2:17; Rom. 6:23) that came into being through “the one having the power of death, that is, the devil” (Heb. 2:14) have been the common plight of mankind. It is not the particular divinely appointed time of death (cf. Eccl. 3:1,2) that Paul is referring to, but the general inevitability of human death. The mortality of man is universal, and the singularity and finality of physical death necessarily (though not necessarily immediately) leads to a final determination, evaluation and assessment of the life that was lived (Lk. 16:22,23; Jn. 5:28,29; Rom. 2:5-11; II Cor. 5:10). Judgment does not necessarily have a negative connotation of condemnation or damnation. The word “judgment” (Greek word krisis, from which we get the English word “crisis”) does not have positive or negative connotations, but recognizes man’s accountability for the consequences of freedom of choice. “God will bring every act to judgment, everything which is hidden, whether it be good or evil” (Eccl. 12:14). It is sin that links death with negative consequences of judgment, but Christ’s removal, abolition and absolution of sin (26) by His own death, allows death for the Christian to be linked to salvation (28) and the confident expectation of hope (3:6; 6:11,18; 7:19). Paul connects the death of Christ to the death of mankind in general, and this is what the Christians in Judea needed to hear as they faced the ominous situation of the possibility of their own deaths in confrontation with the overpowering Roman army. 9:28 Connecting the singularity of human death to the singularity of Christ’s death, Paul continues the sentence, “so Christ having been offered once to have born the sins of many,…” Christ, in conjunction with all humanity, dies once (not repetitively), but His is a representative death whereby He is offered by God (Isa. 53:6,13; Acts 2:23) in the Priestly Self-sacrificing of Himself (7:27; 9:14,26; Gal. 2:20; Eph. 5:2) to vicariously bear the sin consequences for “many.” The “many” for whom Christ has borne the sin-consequences of death, refers to all mankind, not just a few arbitrarily predetermined “elect” as some would have us to believe. Isaiah prophesied that the Suffering Servant would “bear the sins of many” (Isa. 53:12). To the Romans, Paul explained, “the gift of the grace of the one Man, Jesus Christ, abounded to the many” (Rom. 5:15), and “through the obedience of the One the many will be made righteous” (Rom. 5:19). The apostle John wrote, “He Himself is the propitiation for the sins…of the whole world” (I Jn. 2:2). Earlier Paul wrote, “By the grace of God, Jesus tasted death for every one” (Heb. 2:9). This universality of the efficacy of Christ’s death for the sins of all mankind is inclusive of all men other than Himself (7:26,27; 9:7), for He was “without sin” (4:15; II Cor. 5:21), and could thus serve as the sinless representative sacrifice sufficient to remove sin from all the remainder of the human race. This is what Christ accomplished in His first appearance when as the incarnate God-man He put away sin and its death consequences (26), but “He shall be made visible a second time without (reference to) sin, to those eagerly awaiting Him unto salvation.” Jesus was manifested on earth in the incarnation (26), appeared in heaven on our behalf (24), and will be made visible on earth in a second advent. Some would interpret this second appearance of Christ as the coming of divine judgment that was soon to occur in 70 AD (cf. 10:37), but the context of the eternal High Priesthood of Christ seems to indicate a reference to the impending (though not imminent) second physically visible appearance of Jesus Christ on earth, which Christians have expected from the beginning. Since sin and its consequences were removed (26) in the first incarnational coming of Jesus, the second coming of Christ will not pertain to sacrificial atonement for sin and the redemptive efficacy of representative death. The man, Jesus, could only die once (27), and that representative death was totally sufficient to take the death consequences of sin (26). His second coming will serve as the consummation of the salvation made available in the “saving life” of Christ (Rom. 5:10). Christians are already “made safe” from the misused humanity that was enslaved (II Tim. 2:26) by the one having the power of death (2:14), and liberated to function by Christ’s life (Gal. 2:20; Col. 3:4) unto God’s glory, but the removal of all hindrances (Rev. 21:4) to such salvation-living will transpire after Christ’s second advent on earth in the experience of “eternal salvation” (5:9). The eager expectation of Christ’s return can be linked to the return of the high priest on the Day of Atonement. The people of God waited eagerly for the high priest to return from the Holy of Holies, whereupon they were assured that God had accepted the representative sacrifice to cover their sins for another year. Jewish literature records the return of Simon the high priest, “How glorious he was when the people gathered round him as he came out of the inner sanctuary! Like the morning star among the clouds, like the moon when it is full; like the sun shining upon the temple of the Most High, and like the rainbow gleaming in glorious clouds. …Then the sons of Aaron shouted; they sounded the trumpets; they made a great noise to be heard for remembrance before the Most High. Then all the people made haste and fell to the ground upon their faces to worship their Lord, the Almighty, God Most High.” (Sirach 50:5-7, 16,17)In similar manner Christians eagerly await (Rom. 8:25; I Cor. 1:7; Phil. 3:20) the earthly return of the eternal High Priest, Jesus Christ, in glory, already assured of the singular sufficiency of Christ’s representative sacrifice, but desiring to see the completed consummation of salvation unto the ages. By faith they eagerly anticipate “a salvation ready to be revealed in the last time” (I Pet. 1:5), and the privilege of an eternity of worshipping God (Rev. 22:9). Jesus’ final words were, “Yes, I am coming quickly” (Rev. 22:20). 10:1 The third major section (10:1-18) of Paul’s assertion that Jesus is the better sacrifice, sufficient for forgiveness (9:1–10:18), exposes the inadequacy of the Mosaic covenant of Law to do away with a constant reminder of the consciousness of sins (1-4), explains that Jesus’ physical death in accord with the will of God does away with the old covenant sacrifices (5-10), asserts that Jesus’ priestly sacrifice singularly and finally brought mankind to their intended purpose of holiness (11-14), and concludes that the internal provision of the new covenant does away with sin-consciousness and animal sacrifices (15-18). In these four subsections Paul makes the point that the death of Jesus Christ is the termination of all old covenant sacrifices. Paul reiterates what he wrote earlier (8:3-5; 9:23-26), but makes different points of emphasis. “For the Law, having a shadow of the good things coming, not itself the image of those things,…” It is not to denigrate the Law, but to show its deficiency, that prompts Paul to characterize the Law as but “a shadow of the good things to come.” Previously Paul had written that the priests “offering gifts according to the Law, serve as a copy and show of the heavenly things” (8:5). To the Colossians, he explained that the old covenant food laws and festivals were “a shadow of what is to come; but the substance belongs to Christ” (Col. 2:17). Everything in the old covenant arrangement was insubstantial and temporal (space/time) – an unreal profile or outline that prefigured and foreshadowed the good things yet to come in Jesus Christ. The “good things” expected in Jewish eschatology are the “good things having come” (9:11) in Christian eschatology. Jesus Christ is the essential eschatological fulfillment of all the promises of God (II Cor. 1:20), and the essence of all new covenant realities. The “image” or visible manifestation, the form and reality, the substantive embodiment of all that the old covenant Law foreshadowed is realized in Jesus Christ. Jesus is the new covenant substance that cast the old covenant shadow. Christ is the “image” (II Cor. 4:4; Col. 1:15), the visible manifestation of God. All the pragmatic (Greek word pragmatõn) good things (cf. James 1:17) that God intends for man are summed up in Christ (Eph. 1:10), “every spiritual blessing in heavenly places” (Eph. 1:3). Paul is attempting to dissuade the Jewish Christians in Jerusalem from settling for the insubstantial shadows of the old covenant Judaic system. Instead, he wants them to be conformed to the image of the Son” (Rom. 8:29). The Law “by the same sacrifices year-after-year, which they offer repetitively, is never able to make perfect those drawing near.” The old covenant Law and the sacrificial rites mandated by that Law, particularly the repetitive annual sacrifices of the high priest on the Day of Atonement, are ineffectual religious formalities, futile mechanical motions that cannot develop any real personal relationship with God. Those who would “draw near” to the Jewish worship center, sincerely desiring to worship God, can never be “made perfect” by the Jewish sacrifices. They can never be brought to God’s intended objective or end-purpose of bearing His image (Gen. 1:26,27) and glorifying Him (Isa. 43:7) by manifesting His character, apart from Jesus Christ (14). 10:2 “Otherwise” (as is contrary to fact, i.e. the assumption that the old covenant sacrifices were efficacious for perfection), “would not they (the sacrifices) have ceased being offered, because those worshipping would not still have a consciousness of sins, having once been cleansed?” In typical lawyer fashion, Paul asks a rhetorical question which implies and necessitates an affirmative answer, “Yes, of course!” Would not the animal sacrifices have been discontinued as superfluous, their repetition terminated, if they were indeed efficacious to bring mankind into right relationship with God? If you have to do this over and over again, is it really working? The ceremonial sacrifices of the Jewish worship could only cleanse the externalities of flesh (9:13), and could not perfect the internal conscience (9:9). That is why Jewish worshippers continued to have an “evil conscience” (10:22), an on-going consciousness of guilt and shame and condemnation. They continued to have a burdened heart haunted by sin-consciousness. Paul wanted his brethren in Jerusalem to know that their hearts had been cleansed by faith in Jesus Christ (Acts 15:9); their “consciences cleansed from dead works to serve the living God” (9:14). “There is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Rom. 8:1). The sin-consciousness of repetitive confessionalism is indicative of Jewish theology and practice, but Christian theology and worship focuses on Jesus (12:2). Jesus said, “This is the new covenant in My blood. Do this in remembrance of Me” (Lk. 22:20; I Cor. 11:25), not in reminder of your sins! “Why would you even consider returned to the Jewish temple practices and their guilt-producing rituals?” Paul is asking the Judean Christians. 10:3 “In fact, (there is) in those (old covenant sacrifices) a reminder of sins year-after-year.” The Day of Atonement included confession of sins (Lev. 16:21) and humbling (Lev. 23:26-32). Other ritual offerings were a “reminder of iniquity” (Numb. 5:15). The repetition of the sacrifices, whether annually (1,3) or daily (11), kept a continual remembrance of sin in the consciousness of the Jewish worshippers. There was no remission in the old covenant system, just reminder that their sins separated them from God. 10:4 “For it is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins.” This is a concise and succinct denial of the effectiveness of old covenant worship practices. The ritual sacrifices of Judaism offered an external cleansing from contamination, pollution and defilement, but not the internal cleansing and spiritual transformation required to forgives sins and take away sin (10:11). The sacrifices may have provided a temporary and psychological cathartic relief and a religious sense of piety, but only the death of Christ inaugurating the new covenant could “take away sins” (9:26; Rom. 11:27). 10:5 Drawing a conclusion based on the ineffectiveness of the old covenant sacrifices and the sufficiency of the singular sacrifice of Jesus Christ, Paul employs Old Testament scripture as evidence to support his argument. “Therefore, the One coming into the world says,…” Jesus’ “coming into the world” may include a presupposition of His preexistence (1:2; Jn. 1:1), but it is certainly a reference to His incarnational birth (Jn. 1:14), and is a common Johannine expression for such (Jn. 1:9; 6:14; 16:28; 18:37). When writing to Timothy, Paul stated, Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners” (I Tim. 1:5). Using a technique he had utilized earlier (2:12,13), Paul puts Old Testament words into the mouth of Jesus. Since Jesus was instrumental in all Old Testament history and the focal point of all its prefiguring, Paul felt free to project Christ as the implied speaker of the words in Psalm 40:6-8 (quoted again from the Greek translation of the Old Testament [LXX], the Septuagint). His objective is to document and demonstrate that even the Old Testament literature critiques the efficacy of the animal sacrifices. Projecting these words of David into statements of Christ, “He says, ‘SACRIFICE AND OFFERING YOU HAVE NOT WILLED,…” Didn’t God command the sacrifices and offerings of the old covenant? Yes, but as with the entirety of the old covenant, it was provisional to prefigure and foreshadow the sacrificial death of Jesus Christ. Through the prophet Jeremiah, God says, “I did not command your fathers… concerning burnt offerings and sacrifices. But this is what I commanded them, ‘Obey My voice, and I will be your God, and you will be My people’”(Jere. 7:21-23). The primary intent of God was for a people who would obey Him and humble themselves before Him. “Does the Lord take delight in thousands of rams? …What does the Lord require of you, but to do justice, to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God” (Micah 6:,7,8). “Has the Lord as much delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices as in obeying the voice of the Lord? Behold, to obey is better than sacrifice” (I Sam. 15:22; cf. Mk. 12:33,34). God knew what he was going to do to remedy man’s sin problem. “…BUT A BODY YOU HAVE PREPARED FOR ME,…” In solidarity with humanity (2:14), Jesus was “made in the likeness of men” (Phil. 2:7), incarnated in a human body. It was only in a human body that He could be “obedient unto death, even death on a cross” (Phil. 2:8). A textual problem is evident as the Hebrew text of Psalm 40:6 reads, “You have pierced My ears,” while the Greek translation reads, “You have prepared a body for Me.” How, and why, the text was altered is an open question. What we do know is that Paul quotes from the Greek Septuagint (LXX). 10:6 The quotation of Psalm 40:6 continues, “IN WHOLE BURNT OFFERINGS AND SIN-OFFERINGS YOU HAVE NO PLEASURE.” God is not a “God of gore” who takes delight and pleasure in bloody animal sacrifices. Through Jeremiah, God declares, “Your burnt offerings are not acceptable, and your sacrifices are not pleasing to Me” (Jere. 6:20). Through Isaiah, “I have had enough of burnt offerings… I take no pleasure in the blood of bulls, lambs, or goats. …Bring your worthless offerings no longer” (Isa. 1:11,13). “Even though you offer Me burnt offerings, I will not accept them” (Amos 5:22). What does God delight and take pleasure in? “I delight in loyalty rather than sacrifice, and in the knowledge of God rather than burnt offerings” (Hosea 6:6; cf. Matt. 9:13; 12:7). The psalmist, David, writes elsewhere, “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, Thou wilt not despise” (Ps. 51:17). God’s deepest interest is in the spiritual condition of man, and not in the carcasses and corpses (9:17) of animal sacrifices. 10:7 The quotation from Psalm 40:7,8 is continued as the statement of Jesus, “THEN I SAID, ‘BEHOLD I COME (IN THE SCROLL OF THE BOOK IT HAS BEEN WRITTEN OF ME) TO DO YOUR WILL, O GOD.’” Paul uses these verses to show Jesus became incarnate in accord with the prophecies of the Old Testament. The primary emphasis is on the projected statement of Jesus from Psalm 40:8, “Behold I come to do Your will, O God.” This is always what God wanted from man (I Sam. 15:22; Jere. 7:21-23; Hosea 6:6). God’s will is always that His invisible character might be made visible in the behavior of His human creatures, imaged (Gen. 1:26,27) unto His glory (Isa. 43:7). This was accomplished perfectly in the body of Jesus (Jn. 1:18; II Cor. 4:4; Col. 1:15) without sin (4:15; II Cor. 5:21). More specifically, in the God-man, Jesus Christ, God’s will was that the Son should be “obedient unto death” (Phil. 2:8) to be the representative sinless sacrifice, sufficient to remove the sins of all mankind. This was the “will of God” that Jesus came to do. As He approached death, He said, “Not my will, but Thine be done” (Lk. 22:42). 10:8 Paul now dissects the statement from Psalm 40:6-8 into two parts. The first part is the negative comments about the old covenant sacrifices. “After saying above, ‘SACRIFICES AND OFFERINGS AND WHOLE BURNT OFFERINGS AND SIN-OFFERINGS YOU HAVE NOT WILLED, NOR HAVE YOU TAKEN PLEASURE,’ (which are offered according to the Law),…” Paul loosely summarizes Psalm 40:6,7 and lumps together all the various kinds of sacrificial offerings in the old covenant: (1) peace offerings, (2) meal offerings, (3) burnt offerings, and (4) sin offerings, to indicate God’s disdain and rejection of the entire sacrificial system of worship practices, advocated “according to the Law” (9:22; 10:1). Reference to “a body having been prepared” is omitted in this recap, since it will be referred to later (10). 10:9 The second part of the quotation, from Psalm 40:8, is the positive portion that Paul has cast into the Christological context of Christ’s willingness to become the representative sacrifice for mankind. “Then He said, ‘BEHOLD, I COME TO DO YOUR WILL.’” The old covenant animal sacrifices are not in accord with God’s will, but the new covenant sacrifice of Jesus Christ for all mankind is the accomplishment of God’s will. The first and second portions that Paul has divided from the quotation of psalm 40:6-8 are then expanded to apply to the first (8:7,13; 9:1,15,18) and second (8:7) covenants, as a whole. “He takes away the first in order to establish the second.” Paul, the lawyer, chooses his words carefully and deliberately, using juridical language to explain how the first covenant is retracted in order that the second covenant might be enacted. The first is invalidated in order that the second might be validated. The first covenant, the old covenant (8:13), the Law covenant (7:12; 8:4; 9:19,22; 10:1), with all its rules and regulations of external performance “works”, and all its rituals of sacrifices and offerings in the tabernacle/temple worship center, is annulled, abrogated, and abolished. It is taken back, retracted, and done away with, because it served its purpose in planned obsolescence (8:13). The entire Jewish system of religion is displaced, in order to be replaced by the establishment, enactment, and confirmation of the new covenant (8:8,13; 9:15; 12:24) in the representative death of Jesus Christ. In contrast to the first covenant, the second covenant operates by the internal dynamic of God’s grace instead of external Law regulations. The obedience of faith (cf. Rom. 1:5; 16:26) replaces the performance obedience of the works of the Law (Gal. 2:16; 3:5,10). The new worship center allows direct and immediate access to God’s heavenly presence (10:19,20), with the worth-ship of God’s character manifested in human behavior by the grace of God (4:16; 12:15; 13:9,25) to the glory of God (13:21). This is a radical statement that Paul makes. He has jettisoned the entire Jewish religion and replaced it with the eschatological fulfillment of God’s objective in Jesus Christ. What is Paul telling the Christians in Jerusalem? He is categorically asserting that the old covenant and the new covenant are mutually exclusive – antithetical and irreconcilable. There should be no consideration given to returning to the vacuous and worthless practices of Judaism. 10:10 Still emphasizing the second part of the quotation from Psalm 40:8, Paul writes, “By this will we have been sanctified through the once for all offering of the body of Jesus Christ.” Christ’s willingness to be “obedient unto death” (Phil. 2:8) as the representative sacrifice for the sins of mankind allowed for the establishment of the second covenant. The Self-offering (7:27; 9:14) of the physical body (5) of Jesus Christ in sacrificial death was the singular and final (7:27; 9:12) remedial act that removed the sin-consequences from man and ratified the new covenant. Through the death of Jesus atonement for sin has been made, allowing for a reconciled at-one-ment and spiritual union with the Holy God. Christians who have accepted the efficacy of Christ’s death on the cross are “sanctified by faith in Christ” (Acts 26:18). As sanctified “holy ones” or saints (Rom. 8:27; Eph. 1:18; 4:12), they are set apart to function as God intended in the manifestation of His holiness. This sanctification is both an initially received spiritual condition of the Christian (Acts 20:32; I Cor. 6:11), as well as a behavior process of growth in the expression of His Holy character (14; Jn. 17:19; I Thess. 4:3). 10:11 Paul returns to the repetitive and ineffectual sacrifices of the Jewish priest to make a renewed argument for the singularity and finality of Christ’s sacrifice, and its efficacy for the restoration of mankind. “And many a priest indeed has stood day-after-day ministering, and offering the same sacrifices over-and-over again, which are never able to take away sins;…” This initially appears to be a summarizing restatement of 10:1-4, but Paul wanted to emphasize the finished work of the One who was High Priest as well as sacrifice. The Jewish priests stood day-by-day and year-by-year (9:25; 10:3) ministering or liturgizing (Greek word leitourgõn), by offering the same kinds of sacrifices time-after-time. The type of priests (Aaronic or Levitical), and the frequency of their sacrifices (yearly or daily) is not the real issue Paul is addressing; rather, he emphasizes the plurality and repetitiveness of the monotonous sacrifices. The fact that the old covenant priests were standing to do their priestly work will be contrasted with Christ being seated (12). There was no place to sit in the Jewish worship center of tabernacle or temple. Their work was never done, never completed; that because their sacrifices were impotent and ineffective, never able or adequate to take away or cancel sins. Theirs was an exercise in futility, as they calculatingly put the sins of the people in the debit column of last year’s ledger. 10:12 Again, contrasting Jesus to the Jewish priests, Paul writes, “But having offered one sacrifice for sins unto perpetuity, He has sat down at the right hand of God.” As the High Priest in the order of Melchizedek (5:6; 6:20), Jesus offered the sacrifice of Himself (7:27; 9:14). This sinless sacrifice was singularly efficacious as an acceptable expiation and propitiation to remove the sin-consequences of mankind, as well as to perfect and sanctify (14) those receptive to such in order to make them safe from the power of sin. Jesus’ sacrifice in death was singularly efficacious, in contrast to the plurality and repetition of the Jewish sacrifices. Jesus’ sacrifice was efficacious unto perpetuity, in ultimate extension forever, in contrast to the temporality and ineffectiveness of the Jewish sacrifices. The finality and finished work of Jesus’ sacrifice is evidence by the fact that “He sat down at the right hand of God.” As High Priest, Jesus had finished His work (Jn. 19:30) and sat down in the Holy of Holies of God’s presence. This was almost inconceivable to Jewish thinking for they viewed God as an antagonist who was against them because of their sins. They would even tie a rope around the high priest’s leg to pull him out of the Holy of Holies of the tabernacle/temple in case he should die in there while performing his duties on the Day of Atonement. The ever-enduring finished work of Jesus Christ allowed Him to be exalted to the highest place of glory (Phil. 2:9-11) at the “right hand of God” the Father, and to share His authority. Christ is enthroned as the King-Priest in the heavenly sanctuary, an image that Paul uses several times (1:3; 8:1; 12:2; Eph. 1:20; cf. Mk. 16:19). Christians who are “in Christ” are “seated in the heavenlies” (Eph. 1:3; 2:6) with Him, and can likewise “cease from their labors” in order to appreciate God’s “rest” of grace (4:10,11). That is what Paul wanted his readers to understand, appreciate and experience; rather than reengaging in the repetitious, never-ending Jewish practices and causes. 10:13 Thus seated at the right hand of God, our triumphant Lord is “in the meantime waiting, “UNTIL HIS ENEMIES ARE PUT AS A FOOTSTOOL FOR HIS FEET.’’ Drawing again (1:3,13; 8:1; 12:2) from Psalm 110:1, Paul emphasized the completion of Christ’s finished work (Jn. 19:30) by noting that it transcends history and awaits ultimate consummation. The triumph of Christus Victor5 is already complete, yet there is the anticipation of the subjugation of all contrary powers and persons under the authority of the triumphant Christ. Writing to the Ephesian Christians, Paul explained that God “raised Him from the dead, and seated Him at His right hand in the heavenly places, far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and every name that is named, not only in this age, but in the one to come. And He put all things in subjection under His feet, and gave Him as head over all things…” (Eph. 1:20-22; cf. Col. 2:15). To the Corinthians, Paul noted the yet awaited “end, when He delivers up the kingdom to the God and Father, when He has abolished all rule and all authority and power. For He must reign until He has put all His enemies under His feet. The last enemy that will be abolished is death. FOR HE HAS PUT ALL THINGS IN SUBJECTION UNDER HIS FEET” (Ps. 8:6) …And when all things are subjected to Him, then the Son Himself will also be subjected to the One who subjected all things to Him, that God may be all in all” (I Cor. 15:24-28). The “already” and the “not yet” of Christ’s triumph must be kept in Scriptural balance. The embattled recipients of this epistle were caught in the enigma of the interim of the victory of Christ. They were being bombarded by the principalities and powers of religious and political dominion and authority. Paul was warning them not to join the “enemies” who would be ultimately defeated at the feet of Jesus Christ, and encouraging them to participate in the peace and rest of the eternally triumphant Lord. 10:14 The finality of Christ’s finished work objectively in history (and beyond) is now applied subjectively in its effects for Christians. “For by one offering He has perfected unto perpetuity those being sanctified.” Whereas Christ “abides as a priest perpetually” (7:3), and “offered one sacrifice for sins unto perpetuity” (12), now the Christian’s perfection in Christ is declared to be “unto perpetuity;’ a permanent result that carries through forever. There was no perfection of man under the law (7:11,19; 10:1), and the old covenant worship could bring no perfection of the conscience (9:9. Mankind can only be brought to God’s intended objective in their lives by the perfect sacrifice of Christ and the indwelling presence of the Perfect One (2:10; 5:9, Jesus Christ. Thus perfected (Phil. 3:15) in spiritual condition, as “the spirits of righteous men made perfect” (12:23), Christians can “press on towards perfection” (6:1) in behavioral expression. Just as there is an “already” and “not yet” in Christ’s triumph, there is an “already” of Christian perfection in spiritual condition, and a “not yet” of perfect in behavioral expression. Likewise, Christians have “already” been sanctified (10) and set apart to function as God intended in holiness, and “yet” are “being sanctified” in the process of the progression of Christian growth (II Pet. 3:18), pursuing sanctification (12:14) in the consistent expression of God’s holy character in their behavior. 10:15 In this final subsection of the paragraph, Paul quotes again (8:7-12) from Jeremiah 31 to connect the internalizing provision of the new covenant with the absence of sin-consciousness (2) and the abolishment of all Jewish sin offerings (18). Adding to his Old Testament citations to document his case for the superiority of the sacrifice of Jesus, Paul writes, “And the Holy Spirit also witnesses to us;…” Believing “all Scripture to be inspired by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness” (II Tim. 3:16), Paul also understood the Holy Spirit to be the active divine agent who utilized the Scriptures as an instrumental means to provide an evidentiary witness to Christians (3:7; cf. I Thess. 1:5,6). This witness of the written revelation is not the same as the personal revelation of “the Spirit bearing witness with our spirit that we are children of God” (Rom. 8:16), but is the witness of the Spirit through Scripture. 10:16 The witness of the Spirit in Scripture is this: “…for after having previously said, ‘THIS IS THE COVENANT I WILL COVENANT TOWARDS THEM AFTER THOSE DAYS SAYS THE LORD: GIVING MY LAWS UPON THEIR HEARTS, I WILL ALSO WRITE THEM UPON THEIR MINDS,…’” Paul again (cf. 16,17) dissects a text into two parts to make his point. The first part is the quotation of Jeremiah 31:33 which explains that the new covenant that will be made with God’s people after the old covenant period, will not be an external codification of regulations on “tablets of stone” (II Cor. 3:3), and contained in external phylacteries (Matt. 23:5) on Jewish foreheads, but God’s law which expressed His character will be subjectively internalized in “human hearts” (II Cor. 3:3). The divine dynamic of God’s grace for manifesting the character expression of law is received by Christians in Christ. What God desires and wills (5) is inscribed in the minds of Christians, for they have “the mind of Christ” (I Cor. 2:16). 10:17 The second part of the sequence, from Jeremiah 31:34, reads, “AND THEIR SINS AND THEIR LAWLESSNESSES I SHALL NOT AT ALL HAVE REMEMBERED.” In contrast to the constant reminder of sins (3) in the Jewish sacrifices, the new covenant does not foster sin-consciousness (2) and condemnation (Rom. 8:1). The new covenant emphasizes forgiveness and freedom, in a positive focus (12:2) on the Savior, Jesus Christ, rather than on sin. Religious and psychological techniques of introspection to become more conscious of sins and sinfulness have no place in the new covenant experience of Jesus Christ. Yes, there is a proper place for “confession of sin” (I Jn. 1:9) that is brought to our attention by the Holy Spirit, but not for a guilt-producing preoccupation with sins and sinfulness that results in a depressive confessionalism, rather than a vibrant and intimate communion with Christ. How tragic that even in so-called “Christian religion” many revert to wallowing in sin-consciousness, and even accuse those who point to the “finished work” of Christ in the new covenant of a “triumphalism” that is not realistic. 10:18 “Now where there is forgiveness of these things, (there is) no longer (any) offering for sin.” In the inaugurated new covenant there is pardon and release from sins and lawlessnesses (17). The consequences of these are discharged and cancelled, allowing the Christian to operate in freedom and liberty, with bold (Eph. 3:12) and confident (3:6; 4:16; 10:35) access to the presence of God (10:19,20). “There is no longer any offering for sin,” for the offering was made finally and forever in the death of Christ (12). Paul wanted the Hebrew Christians in Jerusalem to know that the repetitive offering of animal sacrifices that were still taking place in the temple there in Jerusalem were monotonous meaninglessness. Even the offering of repetitive confessions for the absolution of sin were of no value. It was extremely important that the Jerusalem Christians repudiate all old covenant practices, for to fail to do so was to deny the efficacy of Christ, and for such apostasy “there no longer remains a sacrifice for sins, but a terrifying expectation of judgment” (26). Concluding Remarks In this extended passage (9:1 – 10:18) Paul lays out his case for the singularity and finality of the representative sacrifice of Jesus Christ – the only means by which man’s sins are taken away, once-and-for-all. The old covenant, with its sacrificial worship practices, could not forgive sins (10:4,11); could not cleanse a person’s conscience from the consciousness of sin (9:9,10,13; 10:2); could not provide access to God, for such was limited to the high priest once a year (9:7,25); and could not perfect and sanctify man to function as God intended (7:19; 9:9; 10:1). The singularly sufficient sacrifice of Jesus Christ, on the other hand, does effect redemption (9:12,15) and forgiveness of sins (9:26,28; 10:12,18); does cleanse man’s conscience internally (9:14) so that there is no consciousness of sins (10:2,17); does provide free access to God, unrestricted, direct, and immediate (9:12,24; 10:19,20); and does perfect and sanctify the believer (10:10,14) to be all that God intends man to be. The finality of Christ’s sacrificial death signifies the end of all animal sacrifices (10:18). His forgiveness of sins is such that these sins can forever be put out of our remembrance, as they are from His remembrance (10:17). The inauguration of the new covenant signifies the complete abrogation of the old covenant (10:9) – “Christ is the end of the Law” (Romans 10:4) – the shadow gives way to the substance (10:1). Christ’s victorious access to the Holy of Holies of God’s presence evidences that God cannot be confined to any worship-box in any religion, but has an “open-door policy” for all who will approach Him through Christ (10:19). What did this mean for the Hebrew Christians in Jerusalem to whom Paul was writing? It was a direct warning that to return to any involvement in the Jewish worship practices would be a denial of Jesus. It would necessarily indicate the apostasy of “standing away from” Jesus, in repudiation of His singular sufficiency. It would be to say that Jesus – His sacrifice, His life – was not enough. Paul will proceed to explain the dire and terrifying consequences of such a rejection. |